Google is introducing a new search result form called Search Generative Experience (SGE). In essence, SGE combines a new display of results with a more extensive application of AI to generate them. The results issue from generative AI – that is, AI that uses text prompts to produce new, multimodal data, where multimodal means “in different formats” (text, audio, image, video).

SGE - Search Generative Experience and how it works

While there is no confirmed date for the roll-out of SGE, experts suggest it might debut at Google’s I/O event on May 14th, 2024. So far, the project is open to the public in 120 countries and operates in seven languages, but members of the public who wish to take part must sign up for the experiments.

“When appropriate,” says Google, SGE will serve up AI-generated “snapshots” to survey the queried topic, provide links and suggest further searches. Moreover, SGE will have a memory so that follow-up searches – even a query like “why?” – can build on earlier searches, with no restatements needed.

SGE will also be pointing out “angles” and “dimensions” for what Google calls “verticals,” citing shopping and “local searches” as examples.

Local searches appear to be searches pertaining to small geographic areas, and so we presume that the results for these will read like highlights from a travel guide, telling the user what’s available and where.

For products and e-commerce, SGE will serve up reviews, ratings, prices and images. How this differs from the usual SGE snapshots is unclear, except that shopping searches will draw on Google’s Shopping Graph: “the world’s most comprehensive dataset of constantly changing products, sellers, brands, reviews and inventory.” (The Graph, says Google, resembles its Knowledge Graph, the database of facts that feeds all other Google searches.) “Some experts who have experimented with SGE state that reviews are becoming more relevant and are being taken into greater account in SGE snapshots.

SGE will influence SEO. With a wealth of information available in SGE, many users may find they do not need to click further for additional information. Investing in content depth, structured information, and data is likely to be advantageous. Additionally, the Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness (E-A-T) formula will become increasingly crucial.

Also unclear is the effect SGE will have on ads, although Google says that they will “continue to appear in dedicated ad slots” and continue to bear the “Sponsored” label “in bold black text.”

For creative endeavors, “users will notice constraints” at the “start” because the company has “placed a greater emphasis on safety and quality.” SGE will generate “up to four” images from a given prompt, with an option to “get” these images “directly in Google images,” but image generation will be available only to users who join the SGE experiment (see above), are at least 18 years old, use Google in English and reside in the US. SGE use in general, however, Google has been extending down to people 13 years of age.

How long has “google” been a verb?

All of the foregoing, says Google, is conditional on the company’s “applying generative AI responsibly,” or “thoughtfully,” or “in accordance with our AI principles,” whose “objectives” are as follows:

- Be socially beneficial.

- Avoid creating or reinforcing unfair bias.

- Be built and tested for safety.

- Be accountable to people.

- Incorporate privacy design principles.

- Uphold high standards of scientific excellence.

- Be made available for uses that accord with these principles.

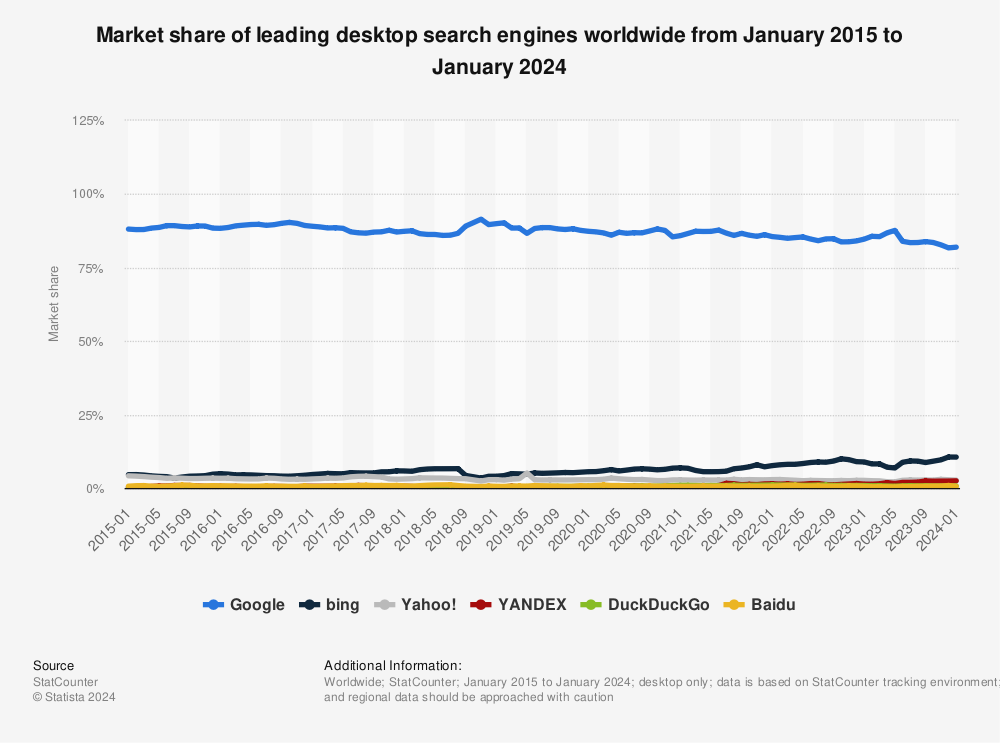

For a normal company in a normal business, these words would retain their facial meaning, at least within the marketing leeway of corporate CSR policy. We might expect a phrase like “Be socially beneficial” to come out of, say, Nike or The North Face. But Google and its parent, Alphabet, do not add up to a normal company, nor do they run a normal business. They maintain a worldwide monopoly on internet searches, which at this point might as well be a monopoly on information.

Find more statistics at Statista

What’s more, Google and Alphabet – like Nike, like The North Face – are not neutral observers of the world. They have a definite point of view – discernable in that same phrase “Be socially beneficial” or, to give one of many examples, on Alphabet’s “All Recipients” page at OpenSecrets.org. This is not a philosophy to let the chips fall where they may. The trouble is that people have always disagreed on the best way for the chips to fall.

Who watches the watchers?

This combination – definite and interventionist point of view, monopoly on information – gives Alphabet/Google world-bending effects, regardless of intent. The company’s very operation determines the meaning of the words in its own pledges – social benefit, bias, safety, privacy, and even science.

How is Google addressing this problem? Well, it isn’t. It has no plans, say, to open its algorithms to public scrutiny. Rather, it is designing systems to improve the fall of the chips.

One method is to set up omissions: “Just as our ranking systems are designed not to unexpectedly shock or offend people with potentially harmful, hateful, or explicit content,” reads Google’s report, “SGE is designed not to show such content in its responses.” The same idea appears elsewhere: “Our automated systems work to prevent policy-violating content from appearing in SGE.”

The company grounds some of these omissions on doubt or danger: “There are some topics for which SGE is designed to not generate a response. On some topics, there might simply be a lack of quality or reliable information available on the open web. For these areas – sometimes called ‘data voids’ or ‘information gaps’ – where our systems have a lower confidence in our responses, SGE aims to not generate an AI-powered snapshot. SGE is also designed not to generate snapshots for explicit or dangerous topics, or for queries that indicate a vulnerable situation – for example, on self-harm queries, where our systems will instead automatically surface trusted hotline resources at the top of Search.” But what qualifies as dangerous?

It is arguable that schoolchildren who play American football are engaging in self-harm. After all, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) – powerful enough to get the US to lock down a few years ago – believes that the sport raises the risk of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. If so, should the NFL, the Pittsburgh Steelers, the Super Bowl or Wilson sporting goods appear in SGE snapshots? What about other companies that have a contract with the NFL, like New Era or ESPN? Are they self-harm-adjacent? If not, why?

And what qualifies as explicit? Should SGE snapshots exclude videos from Gaza, the Donbas or the hearing rooms of the US Senate, where last year a staffer filmed himself having sex?

Google has set finance, health and civic information under a special category, Your Money or Your Life (YMYL), because they require “an even greater degree of confidence in the results.” For example, on health-related queries where we do show a response, the disclaimer emphasizes that people should not rely on the information for medical advice and should work with medical professionals for individualized care.

A human touch

Not everything at Google is automated. It has three methods of “human input and evaluation.” Two of them, “focused analysis” and “red-teaming,” are conducted within the company and, therefore, do not address the information monopoly problem.

The third recalls Meta’s policy of appealing to third-party fact-checkers but seems to have less influence. Google calls on “independent Search Quality Raters” to help “train the LLMs” (large language models) and “improve the experience” but not to change SGE-generated results directly.

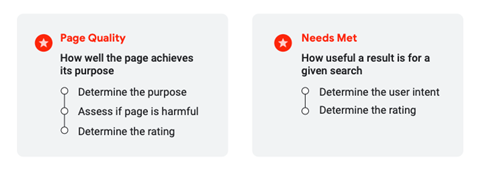

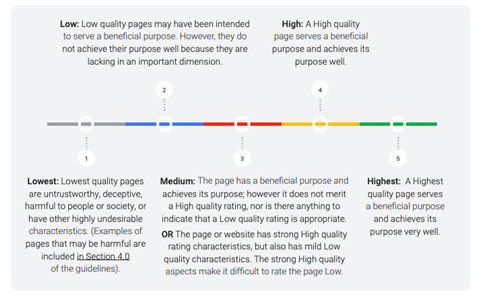

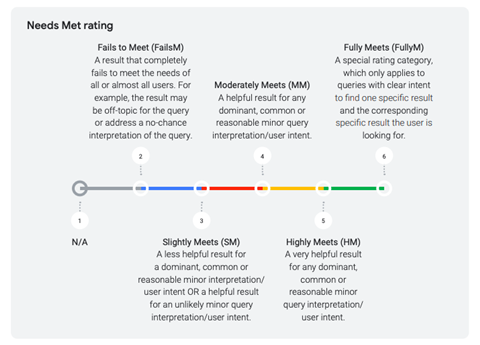

According to Google’s guidelines for this, there are about 16,000 raters in total, with about 7,000 in North America, 4,000 in EMEA, another 4,000 in Asia-Pacific and 1,000 in Latin America. They “represent real users and their likely information needs,” they “collectively perform millions of sample searches,” using “their best judgment to represent their locale,” and they “rate the quality of the results according to the signals we [have] previously established.” This boils down to page quality and needs met, judged on a five- and -six-point scale.