The administration of French President Emmanuel Macron, founder of the Renaissance party, will support a law proposed by an opposition party to penalize fast fashion.

The text in question is no. 2268, “aiming to render fast-fashion out of fashion, thanks to a system of incentives and penalties.” Its proponent is the parliamentarian Antoine Vermorel-Marques, a member of Les Républicains, which was founded and renamed respectively by former Presidents Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy. A debate on the proposed law is scheduled for the National Assembly’s Sustainable Development committee on March 14.

The proposed law is an amendment to France’s Environmental Code and concerns companies that introduce one thousand or more products onto the market in a single day. The cap on the fine levied on an offending company is no longer 20 percent of an item’s purchase price, exclusive of tax, but €5 per item instead.

France’s Ministry of Ecological Transition is, in addition, favorable to a parliamentary initiative both to ban fast-fashion companies from advertising and to ban online influencers from encouraging the purchase of articles of fast fashion. It hopes to compel ultra-fast-fashion companies to post to their websites a “double message,” warning customers of the products’ “environmental impact” and encouraging customers to reuse those products. It seeks to set up a marketing campaign to promote French textiles and decry fast fashion. And, finally, it seeks to put together an international coalition to ban the export of textile waste to countries that cannot handle them sustainably by the terms of the Basel Convention.

The preamble

The law’s preamble speaks of concerns both “ethical and environmental,” France’s “transition from disposable to lasting fashion,” and the “anti-competitive behavior” of fast-fashion companies towards textile producers that opt for sustainability. It speaks of public health, citing a report from Greenpeace according to which many articles of fast fashion contain toxic levels of phthalates, formaldehyde or other chemicals. It speaks also of labor law. And it quotes the current Minister of Ecological Transition, Christophe Béchu, who said in November: “We must combat very powerful narratives, which run totally counter to the model of a sustainable society we ought to be building. […] I am thinking, for instance, of the narrative of fast fashion, which offers a vision of fashion that has absolutely disastrous impacts, and I’m weighing my words on the climate, biodiversity and the oceans.”

The ministry’s website says that the manufacture of a pair of jeans requires 7,500 liters of water, or what a human being drinks in seven years (citing the UN), that one-fifth of all water pollution is due to the finishing and treatment of textiles for apparel (European Parliament) and that 95 percent of the apparel sold in France is imported (Independent Made in France Federation, Union of Textile Industries).

According to Research and Markets’ Fast Fashion Global Market Report for 2024, the fast-fashion market will grow $122.98 billion in 2023 to $142.06 billion in 2024, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.5 percent, and will grow to $197.05 billion in 2028, at a CAGR of 8.5 percent.

The same report foresees virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR), blockchain, AI design, the Internet of Things (IoT), novel ownership models, 3D printing and “heightened demand for manmade fibers” in the market’s future.

The proposed law’s preamble also singles out one fast-growing company, Shein, whose French spokesman, quoted in Le Nouvel Observateur, had this to say in reply: “In its current form, the proposed law does not concern fashion’s environmental impact but does affect the purchasing power of French consumers.” It also, she continued, “targets the business of a few successful actors, with no impact study or evaluation of the true environmental benefits.”

The Sino-Singaporean enemy

Shein is a fast-fashion brand that derives all of its revenues from online sales. It was founded (as ZZKKO) in the Chinese city of Nanjing in 2012 but is now headquartered in Singapore. One of its founders, Sky Xu, now serves as CEO. It maintains offices in Los Angeles, São Paulo, Dublin, Guangzhou, Paris, Washington DC and London. Last month, it opened another American office – for fulfillment and logistics – in Bellevue, across Lake Washington from the Pacific coast city of Seattle. The company employs more than 1,500 people in the US.

Shein operates on what it calls a “small-batch, on-demand production model” and established a supply chain for this purpose in 2014. This now-digitalized system is proprietary, and Shein has paired it with “data-driven merchandise planning” and “customer feedback & analysis” to yield what it calls “a consistently low, single-digit percentage of production waste.” As the company explains: “We do not over-purchase raw materials and any production waste is capped to actual in-demand products.” The initial production run of any article, the company says, is limited to one or two hundred pieces.

According to Business of Apps, Shein’s on-demand manufacturing is farmed out to hundreds of clothing manufacturers in Guangzhou, China. According to the company itself, it has long-term partnerships with “over 5,000” third-party suppliers. Many, if not all, of these do, in fact, seem to be in China, as Shein reveals when speaking of the five international auditors it calls on to conduct “unannounced salary investigations” into its suppliers.

More than selling through an app, Shein does its promotion through influencer partnerships on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest and TikTok, says Business of Apps, and has thereby “captured the social media age better than any other fashion company.”

Moreover, despite its origins and manufacturing base, Shein has no Chinese market, deriving all of its revenue from elsewhere.

Shein says that by 2022 it was the “most searched fashion brand in the world” and operating in “over 150 countries.” By 2023 it had set up a global marketplace for its own products and those of third-party sellers.

According to the data company Earnest, Shein became the top fast-fashion brand in the US over the course of 2021, going from 13 to 28 percent of the market. In so doing, it overtook H&M, which went from 23 to 20 percent. According to Bloomberg Second Measure, Shein increased its lead through November 2022 – and, like other online players, benefitted from the lockdowns when omnichannel players (H&M, Zara, etc.) lost their brick-and-mortar revenues.

In August 2023, Shein acquired about one-third of Sparc Group – parent of Authentic Brands Group (ABG) and Simon Property Group – and Sparc, in turn, became a minority shareholder in Shein.

As Reuters reports, Shein has been seeking to make an IPO on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), at a hoped-for valuation of $90 billion, since about 2020 but has run into obstacles. It is therefore looking also at the exchanges of London, Singapore and Hong Kong. Reuters speculates that Sweden’s exchange, where H&M and Inditex (Zara’s parent) trade, could also be a viable option, but none of the alternatives has been soaring of late like the NYSE or the Nasdaq.

Shein’s revenues for FY 2022, according to Business of Apps, amounted to $22.7 billion, up 44.6 percent year-on-year from $15.7 billion.

Speaking Western

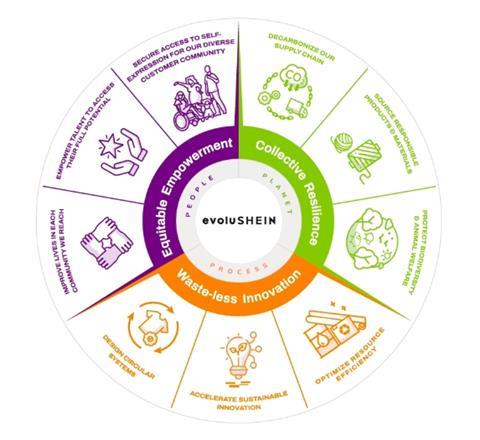

Whatever its conflicts with France, Shein speaks the same language of circularity as its Western competitors. It has set forth a roadmap for circularity called evoluShein. It says that in September 2023, it conducted an “international circularity study” in the “key markets” of Brazil, Mexico, the US, France, Germany and the UK. It says that it is committed to “decarbonizing [its] supply chain, sourcing responsible materials and protecting biodiversity and animal welfare.” And it says it will:

- reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Scopes 1, 2 and 3) by 25 percent by 2030,

- become carbon-neutral in scope 2 by 2030,

- source 100 percent forest-safe viscose and paper-based packaging by 2025,

- ensure all packaging contains 50 percent preferred materials by 2030,

- source 50 percent of Shein-branded products through evoluShein by Design by 2030.

Shein employs a Global Head of ESG, Adam Whinston, whom it quotes as saying: “We are paving the way for our business to continue its growth trajectory and outlining what we can do as a business to drive change. Our Sustainability and Social Impact strategy builds on our existing programs and initiatives across our value chain. evoluShein aims to guide Shein in the next phase of its journey toward a more desirable and sustainable future that is accessible to all.”

Shein also speaks of “equitable empowerment” and its corporate “aim to provide customers around the world with safe access to affordable means of self-expression – regardless of culture, gender, age, body type, ability or economic status.”

The EU perspective

The European Parliament’s Environment Committee submitted recommendations on fast fashion to the rest of the body in April 2023. They include:

- an explicit ban in the EU eco-design rules on the destruction of unsold and returned textile goods,

- rules to end greenwashing through legislation and the regulation of green claims,

- the promotion of “fair and ethical trade practices” through enforcement of EU trade agreements,

- a Commission initiative to prevent and minimize the release of microplastics and microfibers into the environment.