This season’s uniforms for Major League Baseball (MLB), with Nike design and Fanatics manufacturing, are proving to be something of a flop – or a sop. Tops don’t match bottoms, details once specific to a team are now uniform throughout the league, names have shrunk to illegibility from the stands, and fluids once obscured are on display, sometimes in the shape of American states.

Brock Stewart, of the Minnesota Twins, has pitched a game this season with a sweat-induced facsimile of Georgia on his right side. “It’s a downgrade this year, that’s all I’ll say — it’s a downgrade,” Stewart told The Athletic, which has published several such anecdotes. For another pitcher, Andrew Chafin, these days playing for the Detroit Tigers, in the days before the changes, “you picked that up [your jersey], and it was like, Son of a bitch, this is something. […] But now it’s just like, Eh, it’s just another jersey. There’s no special feel to it. You pick it up, and you should feel like you’re putting on a freaking crown and a big-ass fluffy cape, you know what I mean?”

Nike is aware of the sweat-wicking problem and has told The Athletic that it is conducting tests to “lessen the moisture-related aesthetic color differences.”

The company is aware also that the grey uniforms of many teams are of shade A in the jersey and shade B in the leggings. The difference is small but evident in the sheen of the fabrics and is the sort of thing fans notice in a sport with more statistical categories than the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). (Don’t believe us? Look into the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), which offers a primer on sabermetrics, puts out a handbook on research and runs an annual analytics conference.) Nike has “isolated the issue” of the mismatched greys and is “exploring a solution to minimize it,” but there’s more. It turns out the belt loops are different and all the same.

As The Athletic writes, Nike went about “standardizing embellishments and reducing the weight and stiffness of the uniforms. Numbers are smaller and perforated. Names are 2 1/2 inches tall, with a consistent arc. The sleeve trim has changed. Patches are no longer embroidered. And, for some teams, decorative flourishes have been scrapped. The [Philadelphia] Phillies’ chain-stitched wordmark is gone, though the [St. Louis] Cardinals kept theirs.” And Nike has put the kibosh on the special belt loops of both the Atlanta Braves and the aforementioned Tigers, whose little strips had “offered a throughline from Ty Cobb to Al Kaline to Miguel Cabrera.” More statistics than the CBO, as we’ve said, but also more lore than The Lord of the Rings.

So what’s happened?

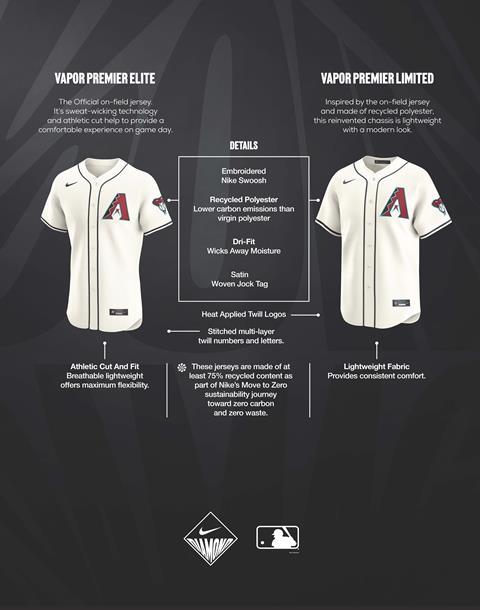

MLB published its own article on the new uniforms in February. As it relates, the history of the so-called Vapor Premier model stretches back six years to 2018 and was, from the start, a joint endeavor between MLB, Nike and Fanatics.

Nike looked at several moisture-wicking fabrics in a quest for lighter weight. Four or five clubs tested prototype jerseys after 2019 Spring Training, and another few clubs at late-season workouts, after their fall from contention for the World Series. The Vapor Premier was to be in official play by 2023, but the lockdowns delayed everything for a year. Clubs received “exact samples of both their home and road uniforms” for 2022 Spring Training, and the MLB Players Association (MLBPA) reviewed them later that season. The MLBPA brought up “minor concerns” but “none involving the issues currently at hand.”

To fit the uniforms, Nike cast aside the traditional hand tool and took up computers – that is, traded the tailor’s tape measure for body scans – “a more accurate approach,” says MLB. However, the manufacturer, Fanatics, took its own measurements last spring – in “an annual exercise” for the subsequent season. The resulting Fanatics database served for 2024’s uniforms.

There nevertheless seems to be a discrepancy of accounts in at least one respect. According to three anonymous sources cited by The Athletic, Nike fitted the pants not player by player but with a division of major leaguers into “four body-type buckets.”

In any case, the lighter, thinner fabric required lighter numbers, letters and patches, so the “thick, embroidered letters, numbers and patches” of ages past gave way to “sleeker and more efficient options” – and club colors gave way to the Nike palette.

No clubs changed their colors officially, but all shifted to Nike standards. Sub-manufacturers had always supplied different twills and such. Now every detail would match every other. “That was all part of the tightening up of the entire process,” according to Stephen Roche, Vice President of MLB Authentic Collection/Global Consumer Products, as cited by The Athletic. “For the first time,” he continued, “we had a uniform where all the colors matched exactly with the hats and the on-field colors. They had always been close, but they weren’t exact. Now they are.”

The Vapor Premier, with its 25 percent gain in stretch and 28 percent gain in drying speed, made its debut at the 2023 All-Star Game. And there were good reviews. Corbin Carroll (Arizona Diamondbacks) said, “I definitely feel faster in it.” Kenley Jansen (Boston Red Sox) said, “It feels more fit on your body, and how light it is,” before comparing it favorably with NBA jerseys. And Jason Heyward (Los Angeles Dodgers) said, “Somehow, this feels even more authentic than the ones that we’ve been wearing, to be honest,” praising the “much nicer” material and the “cool” different texture of the numbers on the back.

As we’ve seen, though, not everyone is happy. “It was Majestic before. It was a smaller company. They’d mainly dealt with baseball,” says Brandon Nimmo (New York Mets). “Then you get a worldwide company that’s worth billions and billions of dollars. And most of the time, they have to answer to somebody who’s all about the bottom line, and they’ve got to make this profitable. I don’t know the whole story, but I just know how business works.”

The whole story, in brief

According to Powers Sports Memorabilia, professional baseball players were getting their uniforms made at home in the 19th century – at their houses, not their home ballparks. At the dawn of the 20th century, the first company to manufacture jerseys and other sporting goods for baseball was the one founded in 1876 by Albert Goodwill Spalding, himself a retired baseball pro. Rawlings entered the game in the 1920s and introduced moisture-wicking and double-knits in the 1940s. Then came Majestic Athletic.

Majestic was founded in 1982 but hit the big time in 2005 when it struck a comprehensive deal with MLB. In exchange for some $500 million, according to Forbes, the company would produce all on-field uniforms at a factory in Easton, Pennsylvania.

Two years later, VF Imagewear, a subsidiary of VF Corp., acquired “substantially all the assets” and “related companies” of Majestic, as the press release reads. In 2015 Majestic renewed its deal for another four years. During that time, in 2017, VF sold Majestic to Fanatics. Finally, in 2020, with Majestic’s renewed deal expiring, Nike secured a comprehensive deal of its own. Fanatics would be part of it, it would last ten years and, according to The Athletic, it would be worth upwards of $1 billion.

Moreover, because Fanatics now owns Majestic, the uniforms would be manufactured in the same old factory. So tradition and continuity – except that The Athletic has another anonymous source, “a person with knowledge of Fanatics’ production process,” who explains that “Nike’s fabric is already dyed when it arrives at the Fanatics factory in Pennsylvania. The pants fabric comes from the same Nike-approved vendor as in prior years, while the new jersey tops are from a separate vendor, as Uni Watch’s Paul Lukas [has] reported.”

A ripping conclusion

According to MLB, which made a statement to The Athletic, Nike is to be commended for its “expertise in bringing innovation and design improvements” and “extensive multi-year process.”

“Nike chose the letter sizing and picked the fabric that was used in these jerseys,” it said, while “Fanatics has done a great job manufacturing everything to the exact specifications provided by Nike,” which will “continue to explore necessary adjustments to certain elements of the new uniforms.”

Added baseball’s commissioner, Robert D. Manfred: “First and most important, these are Nike jerseys. So we entered this partnership with Nike because of who they are and the kinds of products that they use. Everything they’ve done for us so far has been absolutely, 100 percent successful across the board.” The jerseys are “designed to be performance wear as opposed to what has traditionally been worn. So they are going to be different, but they have been tested more extensively than any jersey in any sport.”

Then, last week, the Pittsburgh Pirates played the Detroit Tigers – again, the Tigers! – and Riley Greene, outfielder for Detroit, just had to make a ninth-inning dash from second base, sliding into home and tearing open his pants.