BlockFi, OpenSea, Coinbase, Binance, FTX, Ripple, Impact Theory, Grayscale – all of them companies that have undergone investigation and government-initiated lawsuits over the past couple of years.

The land of crypto, where sports brands have begun to tread over the past few years, is a land of confusion, and not just because blockchain takes some mental focus to understand. The world’s regulatory agencies on financial matters are themselves unsure of what to make of it, and they dislike the uncertainty. The chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Gary Gensler, has referred to the crypto markets as the “wild west,” and his commission seems determined to tame the territory.

In May 2022 the SEC beefed up its freshly renamed Crypto Assets and Cyber Unit with a deputized posse, if you will, expanding the staff from 30 to 50. This unit describes itself as investigating violations of securities law in relation to:

- crypto-asset offerings

- crypto-asset exchanges

- crypto-asset lending and staking products

- decentralized-finance (DeFi) platforms

- non-fungible tokens (NFTs)

- stablecoins (cryptocurrencies pegged to fiat currencies)

Since its establishment, in 2017, the unit has, the SEC says, “brought more than 80 enforcement actions related to fraudulent and unregistered crypto asset offerings and platforms” and thereby generated “monetary relief totaling more than $2 billion.”

The promise of value

One of the SEC’s latest hauls came on Aug. 28, when it charged Impact Theory, a company headquartered in Los Angeles and operating in media and entertainment, with “conducting an unregistered offering of crypto asset securities in the form of purported non-fungible tokens (NFTs).” The operation generated $30 million. The company is complying with a cease-and-desist order for violations of registration provisions of the Securities Act (1933) and has been fined more than $6.1 million in disgorgement, prejudgment interest, and a civil penalty.

As our readers will no doubt recall, several major sportswear brands have been issuing NFTs, ostensibly as collectibles. Impact Theory’s NFTs were called Founder’s Keys and came in three tiers, named with the video-game-like whimsy characteristic of the NFT market: Legendary, Heroic, Relentless. According to the SEC, the company was promising purchasers “tremendous value” if the business succeeded – in other words, they were “investment contracts and therefore securities.”

Unregistered securities present a danger because, according to Antonia Apps, director of the SEC’s New York Regional Office, they deprive investors of “the protections afforded them by the robust disclosures and other safeguards long provided by our securities laws.”

Impact Theory’s founder, Tom Bilyeu, has since tweeted that the company will henceforth be selling digital assets clearly set forth as “collectibles with utility” and “fiercely discourage” customers from treating them as anything else.

Secondaries and fractions

Sportwear brands have at least implied that buying one of their NFTs is like buying a pair of sneakers. Indeed, certain NFTs are designed to have links to specific pairs of physical sneakers. But there are now secondary markets for physical sneakers and other such products, and, according to SEC’s Enforcement Division director Stephanie Avakian, “issuers seeking the benefits of a public offering, including access to retail investors, broad distribution and a secondary trading market, must comply with the federal securities laws that require registration of offerings unless an exemption from registration applies” [emphasis added]. Impact Theory, to obtain its settlement with the SEC, has had to agree never to receive royalties from future secondary-market transactions involving its issued NFTs.

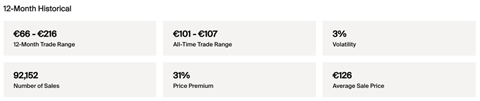

The most famous of secondary market for physical collectibles, StockX, does not yet list sneaker models in the manner of stocks, with a market price, price-history charts and a proper market capitalization, but things appear to be moving in that direction. To take a sneaker model at random, StockX’s listing for the women’s white black panda Nike Dunk Low Retro from 2021 includes a 12-month trade range, an all-time trade range, volatility measured as a percentage, a number of sales, a price premium and an average sales price. The number of sales no doubt counts only transactions on StockX, but it is the next best thing to total shares outstanding. Multiplying it by the average sale price yields a decent measure of a sneaker model’s weight on this market.

There remain differences, though. For instance, it is difficult to see how a “stock split” could occur in the sneaker world – until, of course, equity in individual pairs of sneakers is divvied up into fractional shares.

One argument against NFTs’ being securities is precisely their non-fungible nature. Each NFT being unique, no NFT could substitute for another. By contrast, it makes no difference which particular share of a given class in some company’s stock you sell, buy or hold, because all such shares are the same. As with molecules of water, any one will do. Unfortunately, for this argument, the non-fungibility of NFTs is now being undermined.

As attorneys Andrea Gordon, Sarah Paul and Adam Pollet of the law firm Eversheds Sutherland point out in Bloomberg Law, the advent of the fractional non-fungible token, or FNFT, is upon us – and fractions of a unique NFT are not themselves unique. In other words, fractions are fungible.

Marketplaces already exist for fractional NFTs, such as Fractional.art and LIQNFT, but, at least for now, the fractioning is being done by collectors rather than issuers – through the “smart contracts” that blockchains like Ethereum make possible.

Among the NFTs that have since been fractioned are some produced by Bored Ape Yacht Club, with which Adidas has been associated. As far as SGI Europe has been able to determine, no sportswear brand is at present behind the issuing of fractional NFTs, but the avoidance of issuer fractioning might not be enough to deter the SEC’s scrutiny. The Dilendorf Law Firm in New York has released a statement saying: “Although NFTs are promoted as one-of-a-kind digital assets, certain NFTs currently available in the market may have characteristics similar to ‘passive investments,’” and the SEC, in applying the Howey test, “may conclude that certain NFTs are securities, as it has concluded already with respect to other digital assets.”

According to the Financial Times, moreover, Yuga Labs, Bored Ape’s creator, is “reportedly being probed by the SEC” – for its NFTs as well as its ApeCoin token. SEC commissioner Hester Peirce declined the FT’s request to comment on Yuga Labs, but she did say that:

- some NFTs could in fact be regulated in the manner of stocks or bonds

- NFTs with “governance rights” or offering investors the right to a revenue stream could fall under U.S. securities law

- tokens that are split (fractioned) and then sold off could also fall under the law

Land plus oranges

In determining whether an asset is a security, the SEC looks at two things: the aforementioned Securities Act (1933) and the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in S.E.C. v. Howey Co. (1946). The Howie Company in question was a hotel operator selling interests in orange groves in Florida as real estate. The buyers would then lease the groves back to Howie, and Howie would in turn tend to the cultivation and sale of the oranges. In short, these deals did more than change the name on deeds.

The court ruled as follows: “The test of whether there is an ‘investment contract’ under the Securities Act is whether the scheme involves an investment of money in a common enterprise with profits to come solely from the efforts of others; and, if that test be satisfied, it is immaterial whether the enterprise is speculative or non-speculative or whether there is a sale of property with or without intrinsic value.”

Relief for crypto from the courts?

The crypto world in the U.S. is taking heart from rulings in two lawsuits brought by the SEC: one out of the Southern District of New York, against Ripple Labs, and the other out of the Court of Appeals in the District of Columbia, against Grayscale Investments.

In New York, Judge Analisa Torres has ruled that Ripple’s digital asset, XRP, is not a security in general, as the SEC was charging, but only when sold to institutional investors. This would appear to give some hope to NFT-issuing sportswear companies, as they are not selling Bored Ape NFTs or “virtual kicks” (metaverse sneakers) to hedge funds. It would appear also to be a setback for the SEC.

Ether is to Ethereum – token to blockchain – as XRP is to the XRP Ledger (XRPL). The system is, according to Ripple itself, designed for three things:

- to provide developers with an “open-source foundation” for the building of applications (what we used to call computer programming)

- to provide individuals with an “alternative to traditional banking” and a means by which to “move different currencies around the world” (fund transfers)

- to provide financial institutions with a way to “bridge two currencies to facilitate faster, more affordable cross-border transactions” (forex)

The third of these, according to Judge Torres, is the one that fails to pass the Howie test. Attorney Bill Morgan (@Belisarius2020 on X), among others, is wondering why Ripple shouldn’t appeal the ruling and secure complete vindication. XRP’s institutional use as a bridge currency – its utility, that is, for on-demand liquidity (ODL) – is functional, Morgan argues. Institutions purchase XRP not to make an investment – not to benefit from any appreciation in value – but to make use of a tool. They hold it only briefly, and so such sales of XRP cannot qualify as investment contracts.

The SEC has since obtained permission from the court to appeal, with a trial expected to take place in the second quarter of 2024.

In DC, meanwhile, a panel of three judges ruled this month on appeal that the SEC declined the conversion of Grayscale’s Bitcoin trust, GBTC, into an exchange-traded fund (ETF) on incorrect grounds: namely, as the Wall Street Journal puts it, that “spot markets for bitcoin are unregulated and subject to market manipulation.” Again according to the WSJ, the SEC is now reviewing its options. It could appeal to the Supreme Court, grant the conversion, find other grounds on which to decline it, rescind its approval of bitcoin-futures ETFs or perhaps do something else.

A spot market for bitcoin is a market for bitcoin itself rather than for bitcoin futures – direct vs. indirect purchasing. As he has told CNBC, SEC chairman Gensler sees no problem with bitcoin futures, because they are already under regulation. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) began overseeing them four years ago, and they fall under well-established law, the Investment Company Act (1940).

The coin/alt-coin divide

The use of Ethereum might be the saving grace for sports companies issuing NFTs. The SEC has decided that Bitcoin is a commodity, not a security, and its former director of Corporate Finance, William Hinman, has made a second albeit unofficial exception in the case of Ether, the native token of the Ethereum blockchain. He did this in a speech in 2018 at the Yahoo Finance All Markets Summit:

“When I look at Bitcoin today, I do not see a central third party whose efforts are a key determining factor in the enterprise. The network on which Bitcoin functions is operational and appears to have been decentralized for some time, perhaps from inception. Applying the disclosure regime of the federal securities laws to the offer and resale of Bitcoin would seem to add little value. And putting aside the fundraising that accompanied the creation of Ether, based on my understanding of the present state of Ether, the Ethereum network and its decentralized structure, current offers and sales of Ether are not securities transactions. And, as with Bitcoin, applying the disclosure regime of the federal securities laws to current transactions in Ether would seem to add little value.”

Fortune has called this “the speech that muddied the crypto waters,” because the criterion of decentralization is, as the magazine points out, “nowhere to be found in the statutes that define securities” or in the Howie test.

Moreover, as Fortune reports, a group called Empower Oversight soon discovered, through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, that Hinman was while delivering the speech still on the payroll of the law firm Simpson Thacher, a member of the Enterprise Ethereum Alliance.

The land of confusion, it seems, will remain confused for a while yet. In the general understanding, then, there are two crypto coins – the two biggest ones – and a raft of so-called alt-coins. This could change. Who knows? For now, though, the SEC appears most concerned with the second category.

| Top ten crypto currencies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Symbol | Market cap ($ billion) |

| Bitcoin | BTC | 499.7 |

| Ether | ETH | 194.8 |

| Tether | USDT | 82.8 |

| BNB | BNB | 33.0 |

| XRP | XRP | 26.6 |

| USD Coin | USDC | 26.0 |

| Dogecoin | DOGE | 9.0 |

| Cardano | ADA | 9.0 |

| Solana | SOL | 7.9 |

| Toncoin | TON | 6.1 |

| Source: Coinmarketcap.com (Sept. 5) | ||

Photo by Andrey Metelev on Unsplash